Technical improvement of one’s swordsmanship and fighting skills is impossible without a corresponding change in one’s psychological mind-set. In our style of Shinto Ryu all attacks and counter-attacks, all offensive and defensive movements, need to be executed with the right mind-set: that of iru, entering or going in, or irimi, literally ‘putting in the body’: mentally going towards one’s opponent even when to an observer it looks as if one is widening the distance. On a technical level this means that even when evading an attack one always turns one’s seika tanden, the vital point in-between hara and genitals, towards one’s opponent, while keeping relaxed and breathing out. On a psychological level this means that the student fosters a spirit that runs counter to the natural reaction of a person not trained in martial arts. When someone hits you with a sword or other weapon, it is a normal reaction to cower and attempt to get away, in order to avoid one’s death. A person trained in Shinto Ryu is supposed to enter, to embrace the attacker and open the door for him, to cultivate a spirit that runs counter to his original intuitive reaction of running away. In this sense, he or she is to enter into the jaws of death.

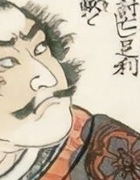

This is an idea that one encounters again and again in the historical writings of Japanese swordsmen, including surviving manuscripts from the Shinto Ryu. The American japanologist William Bodiford, who teaches at UCLA, has translated a few fragments from manuscripts from the Shinto Ryu going back into the 16th century. One scroll, copied by the headmaster Iizasa Murishige (died 1586), reads, in his translation:

Soldiers do not arouse clouds of disagreement.

Caring for illnesses does not extinguish the ember of short lifespans.

Certain death means life, and living means certain death.

Accepting one’s death here leads to a better life. Another scroll explains the idea in an even more mysterious manner:

Attaining self-reliance is walking on sword blades upwards and running over thin ice. This is a marvellously subtle, unobtainable method (…) Keep it secret. Keep it secret.

Of course there is nothing secret about the idea that the warrior should relinquish his fear of death and the attendant stress. It is not specifically Japanese either and runs through all warrior traditions. The Krákumál, a Norse poem that is presented as the death poem of the 9th-century Viking chieftain Ragnar Lodbrok, shows a similar attitude. In the translation of Ben Waggoner:

He who mourns his demise

Never fed meat often

To eagles in the edge-game [the battle]

Ragnar, facing his death in the snake pit where his enemies have thrown him in, cheerfully enters the jaws of death:

On the high bench, boldly,

Beer I’ll drink with the Gods;

Hope of life is lost now – laughing shall I die!

Cultivating this spirit not only enables one to become a good swordsman. It lightens the burden of life, making martial arts practice relevant to the snake pits of everyday life.

Stephen Snelders